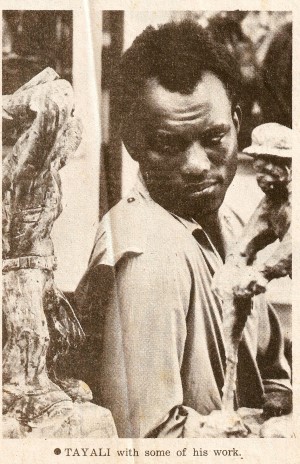

HENRY TAYALI AND FACKSON KULYA:

Academic and folk art in Zambia of the seventies and eighties.

Part 1

Internet publication by Bert Witkamp

Part 2: click here

Art in Zambia series no 4, part 1. No's 1, 2 and 3 are about Fackson Kulya and Henry Tayali; two artists socially at opposing sides of the Zambian art scene of the seventies and eighties. Today Henry’s artistic legacy is still alive and kept alive. In this issue an effort to juxtapose and link Zambia’s best known artist to an artist seemingly bound for oblivion - or is he not?!

At first sight a comparison between Henry Tayali and Fackson Kulya appears unjustifiable as there does not seem to be an appropriate plane for comparison. Yes, there are common elements in their lives: both were Zambian artists, contemporaries (though Tayali was a bit older); and both were sculptors, painters and graphic artists. The differences, however, are much more striking. They lived in very different social worlds with few bridges in between.

|

Tayali (1943-1987) was a well educated, academic artist who lead his professional life in association with the University of Zambia (UNZA) as lecturer and resident artist. He was accommodated by UNZA at Handsworth Court; a pleasant housing complex for university staff adjacent to the university grounds. He, though born Zambian, had spent many years in what at that time was Southern Rhodesia where he went to secondary school in Bulawayo. It was, for an African, quite a feat in the colonial days to access and complete secondary school. This accomplishment alone destined him to become a member of the first generation post independence African élite. The same feat also is a testimony of the foresight, perseverance and ambition of his father who lived to give Henry and his siblings an education that opened up the doors to social advancement and professional achievement. Tayali commenced his academic education in 1967 at the then prestigious Makarere University in Uganda where he obtained a B.A. in Fine Arts in 1971. Two years later he was accepted at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art in what then was West Germany. He was the first African student to receive a German study grant at that state institution. During three years he studied graphic arts and sculpture. Tayali thus had a good share of multi-cultural exposure, an excellent education and knew the international art world.

When he settled in Zambia in 1975 he was from the start accepted as a major, if not the main, indigenous Zambian modern artist. He was welcomed socially by the artistic élite of the day in a scene dominated by people of European background and the new African elite, an élite that in many ways had adopted a western lifestyle including appreciation for the fine arts. These artists and art lovers, African or European, were happy to accept Henry in their midst in a leading role as he was socially and culturally one of them and a genuine, productive artist and native to Zambia. Henry not only belonged to the first generation indigenous post independence élite, he belonged to a considerably smaller group within this class; that of professional people who not only were well educated and had senior positions in society, but also were competent and dedicated to their profession. He from time to time had commissions, sometimes major ones; and his paintings and graphics sold nationally and internationally. Fackson Kulya (born around 1945, died around 1990) also lived for some time at Handsworth Court; not in a residential house but in a servant’s quarter - made available to him by a sympathetic and sympathizing expatriate British lecturer. Fackson was a self-taught artist, an autodidact, born somewhere in Luanshya rural, a Lamba by tribe. He must have had some formal education as he could speak, read and write in English; but definitely not much, if anything, beyond primary school. |

Fackson has never been outside of Zambia, and most of Zambia remained unknown to him. He did not like town life and in the eighties returned to his village near Luanshya. He lived there till he died. He was a villager at heart. In the village you are poor with your fellow villagers; all are the same. In town you are poor because there are rich people; and you depend on these rich people to buy your art.

Fackson and Henry commenced their professional careers almost at the same time, but by then, in 1974-75, Tayali had seven years of academic training behind him while Fackson was learning “on-the-go.” What UNZA was to Tayali – an enabling, inspiring environment – the Lusaka Artist Group (LAG, later the Zambian Artists Association) was to Fackson. In the workshop at the Evelyn Hone College – made available by the College on request of the Art Centre Foundation (a government sponsored body that was to promote the arts) - he met and worked with friends. He now had company in an environment suited to make art work. Here, from 1976 to 1980, he did quite a bit of his learning: how to make lino cuts, use a printing press, make oil paint, prepare for exhibitions, become part of a social network and how to deal with members of the uppa mwamba; the elite, the people who supported him, ignored him or had contempt for him. The small group of Zambian artists at the AFC/LAG studio were all in the same position: no or little formal education in art, newcomers to the scene, trying to make a living out of art in an environment that had little facilities or support for artists. They belonged to the lower strata of society, that of the so-called common folk labelled “the masses” in the political ideology of that time: people with low incomes mostly living in the compounds (townships) spread out over the periphery of Lusaka. These young artists lacked the social skills or even the confidence to adequately deal with the local élite; the educated ones living in the so-called residential areas. At the workshop Kulya must have met Tayali a few times, but there was no communication. Tayali, in his own and in Fackson’s perception as well, belonged to the uppa mwamba, the people on top; with the others including Fackson below; stereotypically poor, dirty, uneducated and preferably voiceless. Kulya never had the security of a stable income and struggled for money all his life. Neither did he have the privilege of holding respected positions in society. Once in a while he was commissioned for sculptures, but he mostly depended on ad hoc sales by personal contacts, hawking, exhibitions usually organised by the Lusaka Artist group (later the Zambia Artists Association), or at the studio at “The College” and in the eighties and nineties through Mpapa Art Gallery - at the time Lusaka’s only art gallery. |

Tayali and Kulya both were hard working, dedicated artists, and indeed, art is the plane that links these two very different human beings. So let’s have a look at their art.

|

Tayali, over time, developed styles ranging from realistic, to free figurative rendering to non-representational. His first work, when he started art as a talented schoolboy in the sixties, was figurative and fairly realistic; with an expressionistic touch. His best known work of that period is the large painting Destiny, now in the collection of the Lechwe Trust.

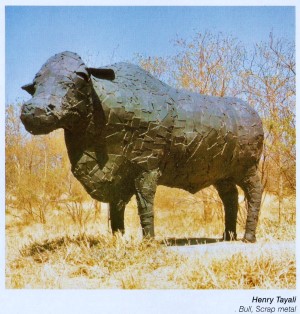

In his mature life this “figurative realism,” or “realistic figuration,” was limited to his sculptural work.

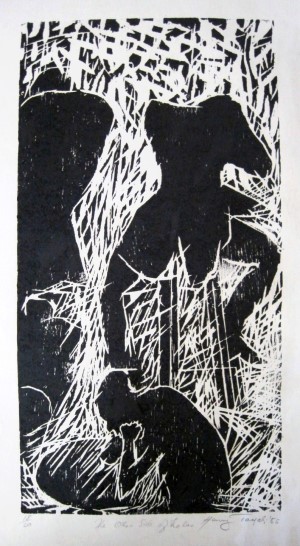

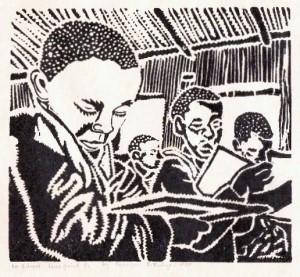

Out of this youthful realistic rendering of scenes either real or imaginary a much freer style evolved characteristic of most of his graphic art. Tayali presumably developed it during his studies in Düsseldorf as this is the style in which most of his post academic graphic work is executed. This work takes off from realistic topics or scenes (i.e., a woman carrying firewood, women gossiping, queuing for food, men drinking in bars &c.) that are executed in his typical dynamic style in which the purpose is not to render the subject realistically but to create an expression of it in which the act of imagery construction at least is as important as the reference to an actual reality. These prints, woodcuts, have clearly outlined main characters that stand out against a background which is made up of free patterns and structures as cut by the gouges and which ideally support the central subject.

|

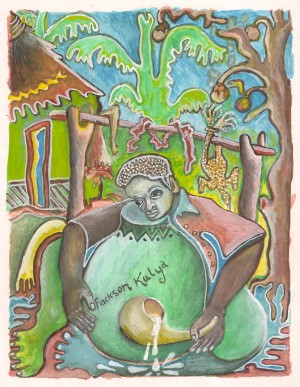

Fackson Kulya’s artistic development does not show such diversity and variety. He evolved right from the beginning a singular figurative

style which drew its inspiration and subject matter out of daily life, folklore and his own fantasy. The extremes within this style hovered between realistic representation of realistic scenes and imagery of fantastic scenes often inspired by folklore or his at times bizarre imagination; the latter being dominant. In school shows Fackson’s variety of realism, The Drunkard (below) his bizarre humour and fantasy. Note how the body of the drinker and the pot from which he drinks his traditional beer are amalgamated into one structure; situated in an almost surrealistic setting.

When I met Fakson in 1975 he was busy experimenting with bronze casting but he soon gave that up – the failure rate was too high and these small bronzes were expensive to make. He did continue to sculpt in wood. Wood sculpting was, however, a technique where his lack of formal and informal education in that medium showed: many of his sculptures have technical flaws such as poor varnish or poor finish in general. Generally I like his graphic art, drawings and paintings better. These media proved a better vessel for his fantastic imagery, the stories he told in pictures.

All of this work appears to be not premeditated; the imagery is drawn or cut spontaneously, in the spur of the moment; it hence never appears to be contrived, and indeed at times naif in its oblivion of aesthetic rules and regulation of the formal world of Academic Art. All of this work genuinely is folk art; art made by a folk artist and presenting folk life, lore, subjects, fantasies and themes. Fackson, lacking the exposure that Henry had, could not but draw his inspiration from what he experienced in his own life and from what he created by his own fantasy. Fackson’s art is local and folksy; Henry’s work is academic and international. |

Continue reading by going to part 2: Click on this link.