HENRY TAYALI AND FACKSON KULYA:

Academic and folk art in Zambia of the seventies and eighties.

Art in Zambia series no 4, part 2

Internet publication by Bert Witkamp

To go to part 1: click here

The left column continues with Tayali, the right column with Kulya.

|

His painting evolved to a form of abstract art or near abstract art, often by super imposing layers of brushstrokes rather than working in planes, sometimes taking off from very basic imagery as shown in photo 5. In this painted silk screen print we can discover “real elements,” such as faces, a tree trunk and hut like structures. The relation between pictorial imagery and “the real thing” is not one of visual and visible similarity. What matters in this kind of work is the way of rendition: how layers of different, superimposed structures combine to create an image the “meaning” of which is contained in itself and not by the reference to a specific concrete event or situation. “Meaning” here is mostly “emotional expression,” or perhaps more accurately “emotional sensation.” In a way one might conceive of his paintings as an abstraction of his graphic style in which the structures and patterns made by gouges now are transformed into brush strokes. Tayali felt his abstract paintings to be highly emotionally charged – a perception not necessarily shared by an observer of these works.

The emergence and development of these styles is related to the environments in which Tayali lived in his formative years. Tayali, at secondary school in colonial Southern Rhodesia, painted the kind of pictures which could be appreciated by his teachers and supporters: it showed talent in a way that they could understand. Tayali, at university and the art academy in the seventies, was exposed to Western art traditions and was influenced by modern and contemporary Western art. His graphic style of figurative expressionism painlessly fits in the pre World War II Western graphic tradition. He applied this style to African/Zambian subject matter (daily life scenes of so-called ordinary people) and in this sense his graphic art combined African and Western elements. The dominant post W.W. II art fashion was abstract art, in particularly a variety labelled abstract expressionism. This strand aimed at “expression” without reference to a visually recognisable reality and at best had only rudimentary figuration in it. The expression had to arise from the “imagery” itself; an imagery that was its own subject matter. Tayali picked this up while studying and moulded it his own way. This kind of abstract art, in the seventies, in the Western world was passé, a thing of the past still practiced of course by recognized masters and pioneers, but not by the next generation of artistic innovators. It was, however, new to Zambia. In Henry’s fifurative work is a strong reference to “the life of the people,” and in particular to its hardships and misery. Certainly this was, in the Kaunda days with its socialist/humanist policies, the politically correct thing to do. Tayali made images about people whose life was familiar to him but which he no longer shared; an almost inevitable result of successfully climbing the social ladder and thereby distancing himself socially and physically of the common folk.

|

Fackson was a man of the people, Tayali was not. Henry was, or had become, an observing outsider. This difference is reflected in the manner both artists present people. Fackson did not portray the so-called common folk as poor, down trodden, ugly or miserable. He portrayed them as human beings in a fantastic, humorous, bizarre and imaginative world. Look at the reproductions below.

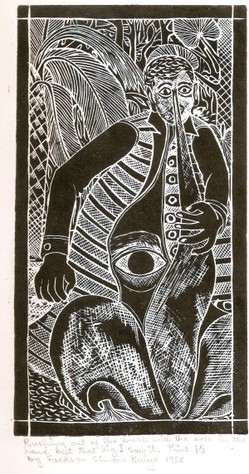

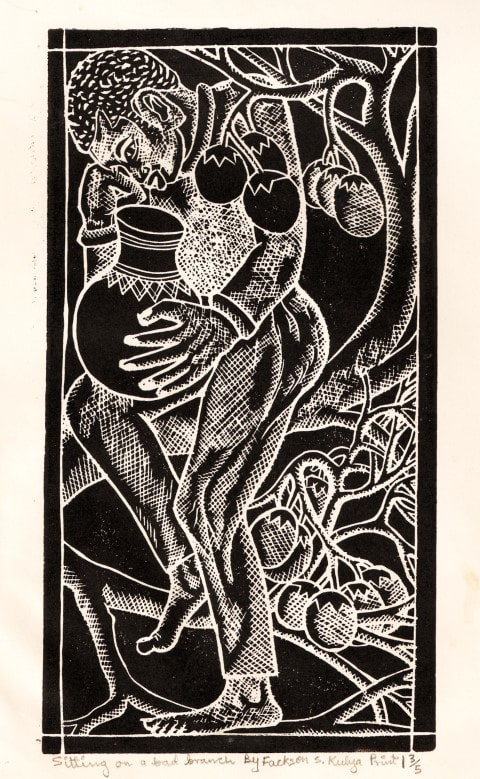

Photo’s 8 and 9 illustrate Fackson’s at times bizarre imagination. Both linocuts are made around 1988, about a year after Tayali’s death. The full title of the linocut reproduced on Photo 8 is “Rushing out of the bush with the nose in the hand but that big I saw it.”

The print of photo 9 is titled “Sitting on a bad branch.” The prints, from the point of view of conventional “academic” composition, are uninteresting, and the print of photo 8 at art school would be a failure in that regard. The deliberate arrangement of visual elements into an interesting, intriguing, balanced structure is absent; instead we see what could be called a spontaneous visual narrative. What redeems the prints is originality, humour and locality. They are Zambian prints by a Zambian artist; original because the imagery could only have arisen in Fackson’s mind and one (no 8) is funny, even incorporating a pun on the I – eye. The imagery does not picture the human being in its degrading or pitiful aspect. The men in the pictures are men in a story in fantasyland; an intriguing place where anything is possible - unlike in practical reality where only money buys you food, education, health care and generally a comfortable life. Money does not, however, according to a famous band “buy you love.” Neither, I would say, does it buy you artistic fantasy, imagination or talent. Fackson, poor as he was, had these rich artistic gifts.

As a note to the above I add that often the aspect of “composition” is low keyed in Fackson’s work. Fackson’s two dimensional work is visually structured by its unfolding narrative, not by superimposed compositional regulation or aesthetics. “Composition” also is not an aspect of outstanding interest in Tayali’s graphic work, but his prints do not confront you with the lack of it. |

A note on abstract art and academic education

|

Fackson’s deficient formal education and exposure in Fine Art indeed had fortuitous side effects. It preserved his originality and prevented him from adopting styles not his own. There is, indeed, a great divide between Fackson’s bizarre, humorous, fantastic, figurative imagery and Henry’s emotionally charged brush strokes which are mostly so charged only for Tayali himself. One trouble with abstract art is that you have to be very, very good to make interesting, lasting work; or you must be truly original thus making your work last by its originality; and of course the best is to have both qualities. Tayali was not a pioneer of abstract expressionism. He joined an ongoing and established style/movement – at its post avant garde stage. His role in it is local or localised, not international. His expressionist abstract fathers, artists such as Willem de Koning and Jackson Pollock in the USA or Karel Appel and the Cobra movement in Western Europe, had done the pioneering

|

work of a movement whose very foundations left very little space for future innovative development in the same style. Post World War II “abstract art” in the expressionistic vein simply was the realisation of one of the theoretically possible extremes in Art; and once it was done, that was it.

Fackson’s lack of exposure, his very provincialism, kept him out of this Western artistic extravaganza. A picture, to him, was not an element of an artistic discourse or an exploration of logical possibilities of the artistic discourse. Neither is it the ultimate expression of an individual sentiment or state of mind. A picture, to him has a story to tell, often actually was a visual story; and in that sense is the opposite of abstract art which by its very exclusion of figurative association had no story to tell other than the sensation of its perception; and such sensation fundamentally is non-verbal. |

In the eighties, had asked anyone in the inner Lusaka art circle: “Who is the better artist, Tayali or Kulya?” chances would have been that even amongst the artistic in-crowd some would have asked “Kulya – who is that?” For most the answer would have been, without hesitation: “Tayali of course.” And they would have considered the question ridiculous and out of place.

|

What I have tried to tell you in this text is that it is not that simple; and if it is not that simple the question might be wrong. Perhaps the question should be something like: “What are the outstanding, lasting qualities of the art work of these two artists? Fackson had qualities that mattered which Tayali did not have; and surely, the reverse is also true. So true that we can let Fackson fade away out of the recent history of Zambian modern art? That, in my judgement, is carrying things too far. Fackson’s work much more than Tayali's, has locality, it is Zambian; not just because it was made in Zambia by a Zambian artist, but because it connects to traditional culture and oral traditions in particular; his imagery is made the way stories, riddles or songs are made. He thus contributed to an approach to art that builds upon Zambia's cultural heritage. In so doing he presented the so-called common (wo)man as a person of interest, even of marvel and not, as so often in Tayali, as a being which at best deserves sympathy by its misery; living in squalor, struggling for survival. Two complementary artists indeed, and of each you can say that “the same thing that makes you rich makes you poor.” Kulya's station in life enabled him to make genuine imagery about folk life and culture but excluded him from obtaining the social skills and education necessary to function in the higher strata of society – and make a lasting name for himself by himself.

Notes:

1. Article was first published in 2013 as a post in the Art in Zambia Blog. 2. The author is a cultural anthropologist and artist who has worked in Zambia during 1975 – 1980 and as of 1988 till the present. He publishes on The Net about art in Zambia and material art technology. Bibliography and references Barde, Bob (1980). "Henry Tayali: Zambian Printmaker". African Arts (UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies Center) Vol 13 (3): p. 82. Ellison, Gabriel (supported by the Book Committee of the Visual Arts Council of Zambia) (2004). Art in Zambia. Lusaka: Book World Publishers. Kennedy, Jean (1992). New Currents, Ancient Rivers: Contemporary African Artists in a Generation of Change. Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 978-1-56098-037-7. Leyten, Harrie and Paul Faber (1980). Moderne Kunst in Afrika. Amsterdam, Tropen Museum Wikipedia. (2013). Henry Tayali. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Tayali Witkamp, Gijsbert (2015). The Lusaka Artists Group. http://artblog.zamart.org/2015/07/the-lusaka-artists-organisation.html Zaucha, Grazyna (1996). Zambia: identities in print. Gallery, no 8, pp.11-13. |

Tayali, whose very training and exposure lead him to make art that was international and provided him with the means to socially be a leading figure, a member of the uppa mwamba and an achiever, by these very same privileges lost touch with the life of the common folk who in his work often are depicted in their negative aspect. You may ask whether his choice of daily life scenes as subjects is motivated by compassion for the cause of the “wretched of the earth,” or that his true commitment simply is in the art of imagery construction. I believe the latter to be true, though not to the exclusion of a social commitment.

Here then we find the plane where both artists are different yet equal: each one lived to make art as art; not as ideology, not as realistic representation of real scenes or unrealistic representation of real scenes, but to create artistic imagery the meaning and value of which is principally contained in itself. |