KEEPING ART: the care of prints, drawings & watercolours

Author: Bert Witkamp

Version: 2 September 2013

Zamfactor Ltd. Technical Art Bulletin no. 1.

This publication can also be accessed at the ZamArt Blog at http://artblog.zamart.org

Parts of the contents of this leaflet may be quoted with reference to its source, but extensive reproduction in whatever form, as by photo copying, scanning, Internet publication or printing is forbidden unless the author / Zamfactor Ltd. has consented to such reproduction in writing.

In this text we first consider framed art behind glass on display; next is framed and unframed art in storage.

1. Purchased framed art with glass

A note on abstract art and academic education

|

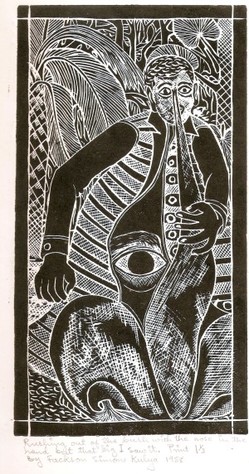

Fackson’s deficient formal education and exposure in Fine Art indeed had fortuitous side effects. It preserved his originality and prevented him from adopting styles not his own. There is, indeed, a great divide between Fackson’s bizarre, humorous, fantastic, figurative imagery and Henry’s emotionally charged brush strokes which are mostly so charged for only Tayali himself. One trouble with abstract art is that you have to be very, very good to make interesting, lasting work; or you must be truly original thus making your work last by its originality; and of course the best is to have both qualities. Tayali was not a pioneer of abstract expressionism. He joined an ongoing and established style/movement – at its post avant garde stage. His role in it is local or localised, not international. His expressionist abstract fathers, artists such as Willem de Koning and Jackson Pollock in the USA or Karel Appel and the Cobra movement in Western Europe, had done the pioneering

|

work of a movement whose very foundations left very little space for future innovative development in the same style. Post World War II “abstract art” in the expressionistic vein simply was the realisation of one of the theoretically possible extremes in Art; and once it was done, that was it.

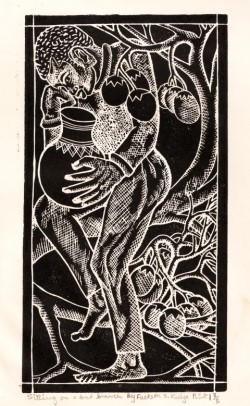

Fackson’s lack of exposure, his very provincialism, kept him out of this Western artistic extravaganza. A picture, to him, was not an element of an artistic discourse or an exploration of logical possibilities of the artistic discourse. Neither is it the ultimate expression of an individual sentiment or state of mind. A picture, to him has a story to tell, often actually was a visual story; and in that sense is the opposite of abstract art which by its very exclusion of figurative association had no story to tell other than the sensation of its perception; and such sensation fundamentally is non-verbal. |

In the eighties, had asked anyone in the inner Lusaka art circle: “Who is the better artist, Tayali or Kulya?” chances would have been that even amongst the artistic in-crowd some would have asked “Kulya – who is that?” For most the answer would have been, without hesitation: “Tayali of course.” And they would have considered the question ridiculous and out of place.

|

What I have tried to tell you in this text is that it is not that simple; and if it is not that simple the question might be wrong. Perhaps the question should be something like: “What are the outstanding, lasting qualities of the art work of these two artists? Fackson had qualities that mattered which Tayali did not have; and surely, the reverse is also true. So true that we can let Fackson fade away out of the recent history of Zambian modern art? That, in my judgement, is carrying things too far. Fackson’s work much more than Tayali's, has locality, it is Zambian; not just because it was made in Zambia by a Zambian artist, but because it connects to traditional culture and oral traditions in particular; his imagery is made the way stories, riddles or songs are made. He thus contributed to an approach to art that builds upon Zambia's cultural heritage. In so doing he presented the so-called common (wo)man as a person of interest, even of marvel and not, as so often in Tayali, as a being which at best deserves sympathy by its misery; living in squalor, struggling for survival. Two complementary artists indeed, and of each you can say that “the same thing that makes you rich makes you poor.” Kulya's station in life enabled him to make genuine imagery about folk life and culture but excluded him from obtaining the social skills and education necessary to function in the higher strata of society – and make a lasting name for himself by himself.

|

Tayali, whose very training and exposure lead him to make art that was international and provided him with the means to socially be a leading figure, a member of the uppa mwamba and an achiever, by these very same privileges lost touch with the life of the common folk who in his work often are depicted in their negative aspect. You may ask whether his choice of daily life scenes as subjects is motivated by compassion for the cause of the “wretched of the earth,” or that his true commitment simply is in the art of imagery construction. I believe the latter to be true, though perhaps not to the exclusion of a social commitment.

Here then we find the plane where both artists are different yet equal: each one lived to make art as art; not as ideology, not as realistic representation of real scenes or unrealistic representation of real scenes, but to create artistic imagery the meaning and value of which is principally contained in itself. |